Esta web utiliza cookies para que podamos ofrecerte la mejor experiencia de usuario posible. La información de las cookies se almacena en tu navegador y realiza funciones tales como reconocerte cuando vuelves a nuestra web o ayudar a nuestro equipo a comprender qué secciones de la web encuentras más interesantes y útiles.

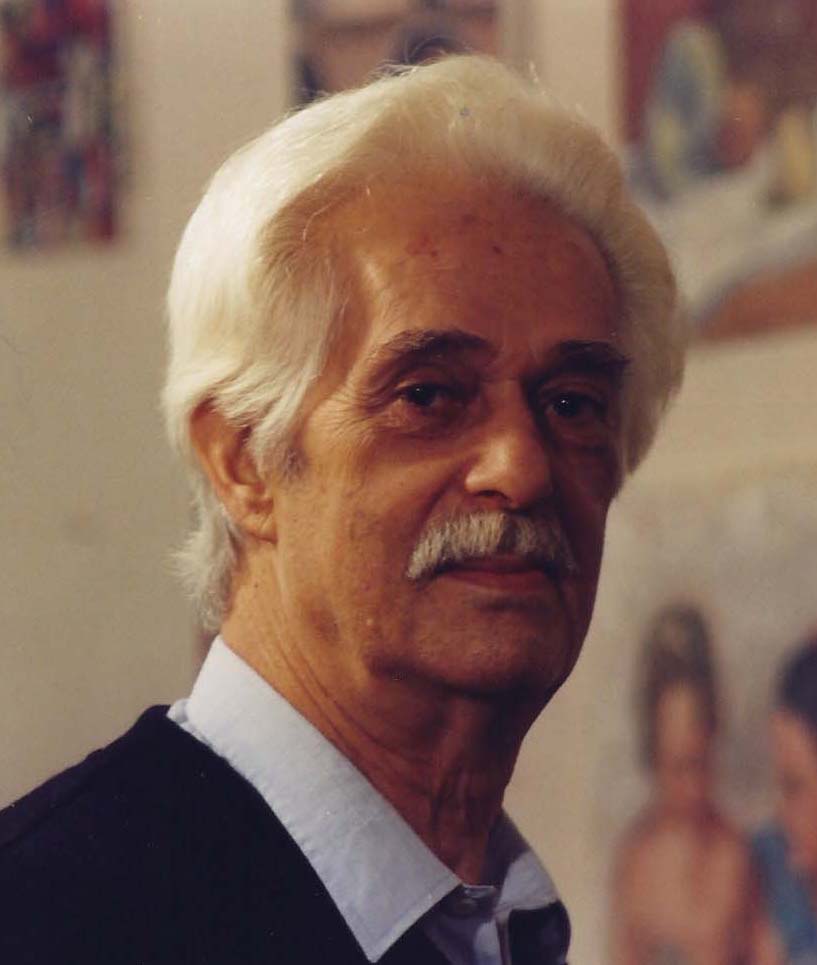

Alceu Ribeiro: Resembling himself.

(Uruguay, 1919 - Palma, 2013)

His early life took place in the countryside, somewhere far from civilisation, near the Uruguayan border with Brazil. He recalls himself and his brother drawing the chickens, dogs, rabbits and cows at the farm where his parents worked, in a timeless place with no limits.

He would have probably spent his whole life there if it hadn’t been for this particular visitor to the farm, a Justice of the Peace, who was amazed by their natural drawing skills; he arranged their relocation to the capital and granted them scholarships to study Fine Arts.

Here it is important to mention a great Uruguayan painter, Torres García, who lived many years in Barcelona, and then returned to his country to become a teacher.

His numerous treatises, his theoryyof constructivism, his wish to pass on to his pupils everything he had learned from the great masters and his own experience; all these made him the teacher who introduced a whole generation of Uruguayan painters to modern art. In Uruguay it is said that there is a before and an after Torres García, with whom Alceu Ribeiro studied under for ten years. Alceu remembers both his leading figure and personality with unfading devotion: «He was a man of great generosity and one of the great masters of our century. Picasso, Miró and Torres García, especially the latter for his teaching work. Without him we could hardly speak of modern Uruguayan painting». At the end of every statement, he always brings up Torres García; a quote from him, an observation, a lesson. He learned from Torres García that all true painting is abstract, and that is because a figurative work does not copy reality, but rather takes references from real life that give an impression of reality. «Velázquez is a great abstract painter, especially in his later works. Not to mention Goya. All paintings worthy of this name are abstract. Later on, it may or may not be figurative».

Art is the opposite of chaos.

He inherited from Torres García his love for teaching, and for many years he taught at the Universidad del Trabajo in Montevideo, just like he does nowadays at his workshop in Palma. «It is true that it takes up a lot of my time, but somehow it is time well spent, because it demands a high level of intellectual discipline: it forces you to specify what you want to transmit, and students are those who often bring up the toughest problems, i.e. the most stimulating ones. In any case, teachers must restrict themselves to passing on their knowledge, in order that students, once they have this essential tool, can later develop their own personalities. It is almost a miracle to create a significant work of art without craft. And craft teaches, above all, to organise the painting: an unorganised surface can never be transcendent. Torres García endorsed a quote by Bracque, who said that rule must correct emotion; and another by Stravinsky, who proclaimed that art is the opposite of chaos. The great works of art history are perfectly organised, nothing in them is unnecessary». Discipline, that is, and work, with knowledge of the craft. Any work by Ribeiro follows these fundamental laws. It is based on a first sketch «which is not exactly a sketch, but a preliminary document, which is usually of a naturalistic character. From this document will come an initial idea of what the painting should be, its potential ways of organisation, which are only three: projecting shapes on the background, juxtaposed or superimposed. There is a preliminary study of colour…, and that’s the starting point. From then on, you may or may not be an artist. Up until now the craftsman was the one who worked. Now it is the artist who has to start their work, because if all their previous ones are concluded in a really well done work, but are incapable of transmitting an emotion to the viewer, or making them feel an aesthetic pleasure, then all the work has been useless».

He also inherited visible influences from Torres García in his work, in which Picasso, Bracque, Matisse have also left their mark: a combination of methods which finally result in a unique style, a style «which is the very personality of each painter, and which, yes, in a certain way is an inevitability». At sixty-five, Alceu considers himself an apprentice, and sometimes «I allow myself a moment of vanity when I look at my works believing that some of them already look a bit like me”. Alceu Ribeiro has been living in Majorca for six years. He affirms that he feels at home on the island and that he can calmly resist the irregular onslaughts of nostalgia over his homeland. His workshop is bathed in the light of an Alcoverian courtyard, a desolate garden with a «dry fountain”.

The reason why he has not fit more into the island is due to his shyness, but not due to any kind of rejection by the Majorcans: it would be unusual for a man like Alceu Ribeiro to be subject to rejection, since he did not made up any glorious past and sticks to the principles of Franciscan modesty.

His work has not been widely exhibited in our galleries. These days, however, spectators have the opportunity to contemplate a great exhibition of Ribeiro’s work at the Bearn Gallery. The opportunity to meet an artist who offers a true exhibition of his craft mastery and who is also capable of transmitting emotion beyond rules. The exhibition is made up of a set of wood «the making of which has been a very interesting experience. Interesting for me, because painting requires a very focused release of tension: it doesn’t take long. Wood is slower and more unpredictable. Once you have cut it and placed it on the surface that supports it, it’s still nothing, or it’s simply a wood that doesn’t transmit anything. If you want it to transmit something, you have to work it, make it suffer, and paint over it so that the colour does not spoil the sensation of volume. This whole process requires a very measured tension over time. My point is that without the craft it would be impossible to make these works, but what remains of them, in the end, is not their execution; it is what they transmit».

Text: Guillem FronteraText: Guillem Frontera, Diario de Baleares 26 of May of 1985